blog

Apparent probability

2015-07-27

Anecdote

Let’s say you are creating a computer game where the player explores a dungeon and every time he finds a new treasure chest there is a 10% chance it contains a rare item. A naïve implementation goes like this:

public bool ContainsTreasure() {

return (random() < 0.1);

}

Fairly straightforward, right? And it certainly fulfills the desired property of spawning 10% rare items. But soon the complaints of players roll in.

I have opened 40 chests and not a single one of them had a rare item in it. This is not 10%! My game is broken.

Perceived unfairness

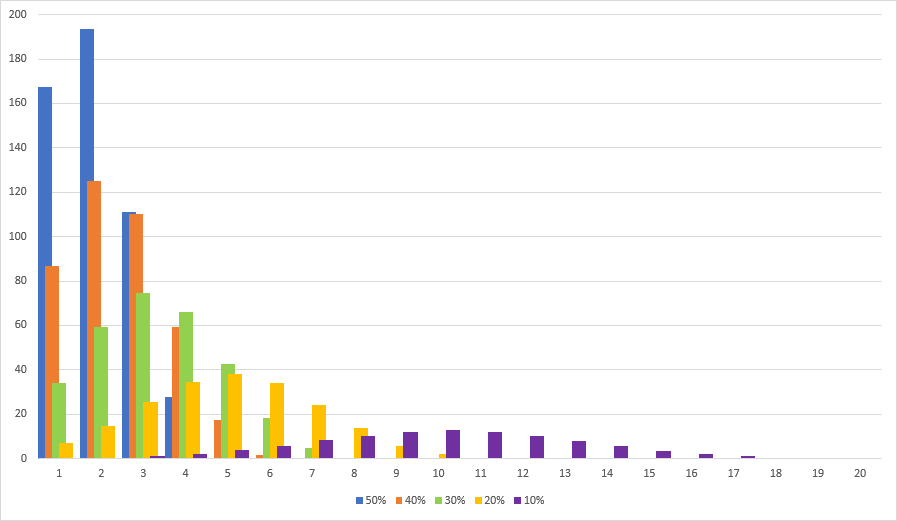

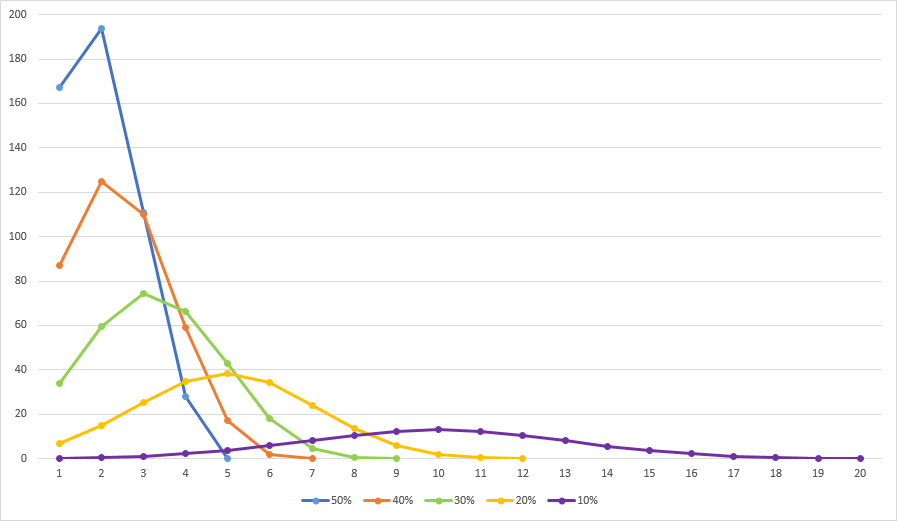

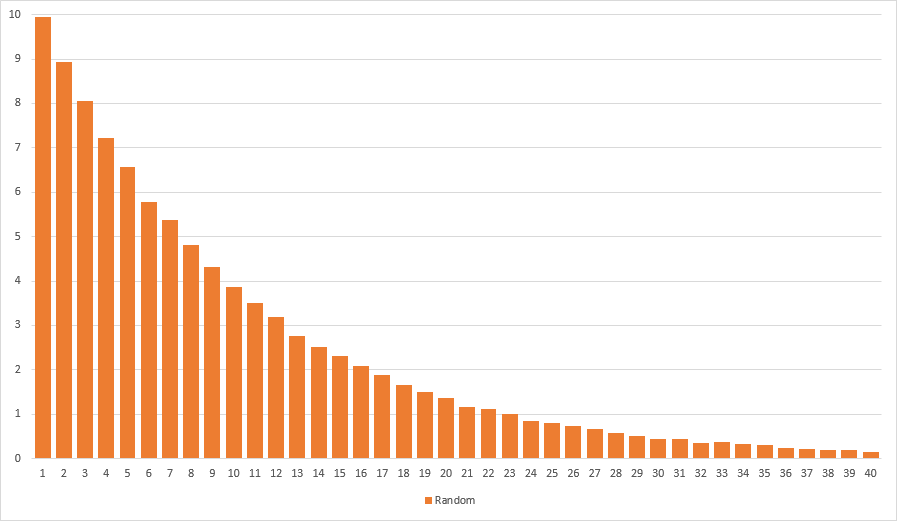

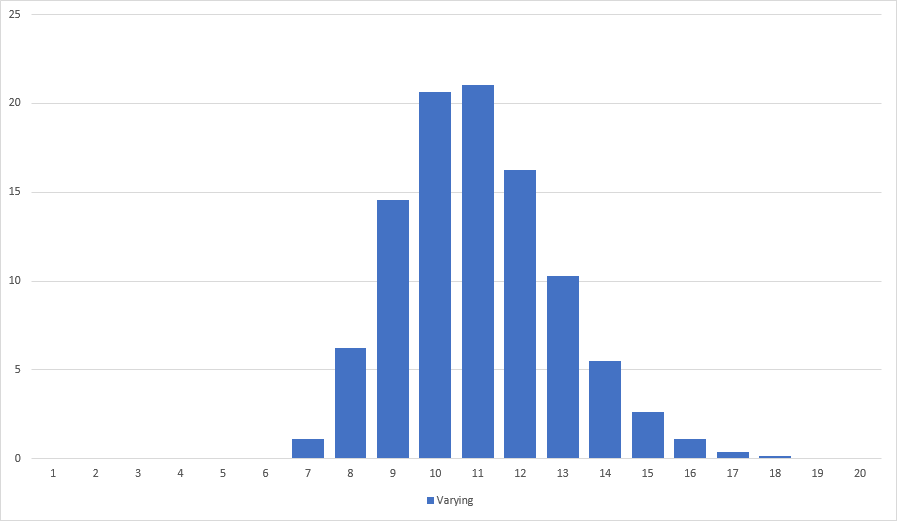

Clearly there is nothing wrong with the implementation. It yields rare items with 10% probability on average. In fact running statistics on a sample of one million evaluations the expected value of treasure chests to open until finding a rare item is ten. So all is good, right? Wrong. Always look at the variance too! Turns out the variance is above 90, which basically means anything can happen. Let’s graph the probability of having to open x number of treasure chests until finding a rare item. Here is what the distribution looks like:

It’s easy to see that most of the time it takes less than 22 treasure chests to find a rare item. But what about the rest of the time? All bets are off. In fact I had to crop the graph to make it fit. The actual distribution continues way further to the right. There is a small chance that it will take 40, 50, 100, or even more chests to find that rare item the player so dearly desires. One out 100 players will encounter this situation and get angry.

This is bad, but what can we do? Let’s take a step back. What we really want can’t be captured by a mere 10% chance. What we want is a game experience where it takes roughly ten treasure chests to find a rare item. We don’t want everlasting streaks of bad luck. We don’t want long streaks of good luck either. Oh, and we don’t want it to be predictable. It should feel random but fair.

Dithering

A good idea when trying to exert control over randomness is to start with something deterministic and then add a bit of randomness on top. Dithering is a deterministic process to generate a series of events. In our case there is only one event: loot or no loot. The implementation is as follows:

public bool ContainsTreasure() {

entropy += 0.1;

if (entropy >= 1) {

entropy -= 1;

return true;

}

return false;

}

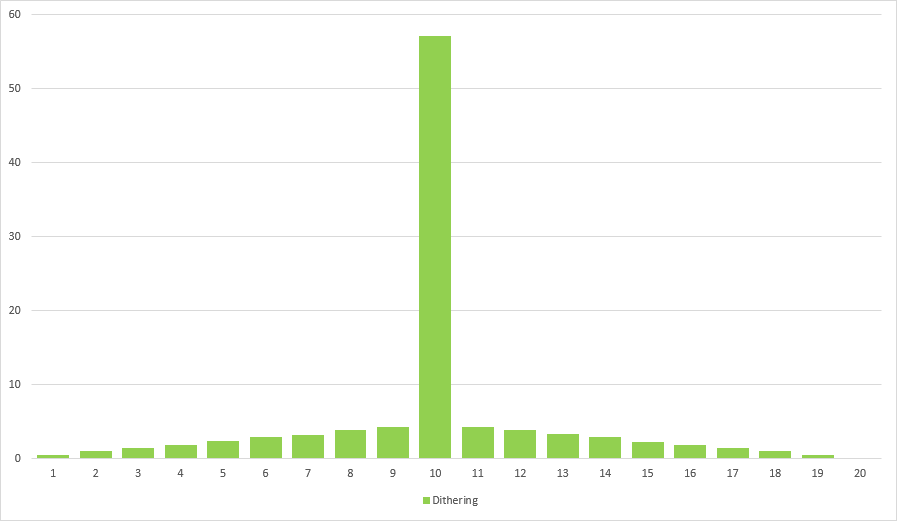

Again fairly straightforward. Every time a chest is opened we add 10% to the entropy until its above 100%. This will put a treasure in every tenth chest, which is great because we managed to prevent streaks of good/bad luck. But it’s also really boring. Nevertheless there are real games using dithering, in this case for calculating the chance to dodge an attack. To make combat a bit less predictable the entropy variable is reset to a random value before each fight. Here is what it looks like:

Resetting the entropy to a random value every now and then is still not great. If done too often we are back at the initial situation, if not done often enough everything becomes predictable.

Adding randomness

Of course there are other options of adding randomness than messing with the entropy. One option is to randomize the success chance so that its expected value is 10%. Let’s call it varying. Examples are:

entropy += 0.1 * random(0, 2); // Option 1

entropy += 0.1 + random(-c, c); // Option 2

Where random(a, b) returns a random value between a and b. Suffice to say that the former does not prevent endless streaks of bad luck and the latter needs very careful tuning of c. In any case both solutions make it impossible to score twice in a row. They are not random enough. This is how the first one looks like:

Another option is to deal a deck of cards. The deck is filled by using the deterministic dithering algorithm. Every time a treasure chest is opened a random card is drawn from the deck to determine the chests content. The deck is refilled using dithering. It is the perfect solution to prevent really long streaks of good or bad luck. The tricky part choosing the right size for the deck. Big decks play the naïve randomness, small decks play like dithering. In addition a deck based implementation needs more memory than other solutions. I tried something else.

Threshold

There is another straight forward option of adding randomness to the dithering algorithm. It is this line:

if (entropy >= 1) { ... }

What happens if we choose a random threshold with an expected value of 1? Well, turns out to be perfect. Implementation:

public bool ContainsTreasure() {

entropy += chance;

if (entropy >= random(1 - c, 1 + c)) {

entropy -= 1;

return true;

}

return false;

}

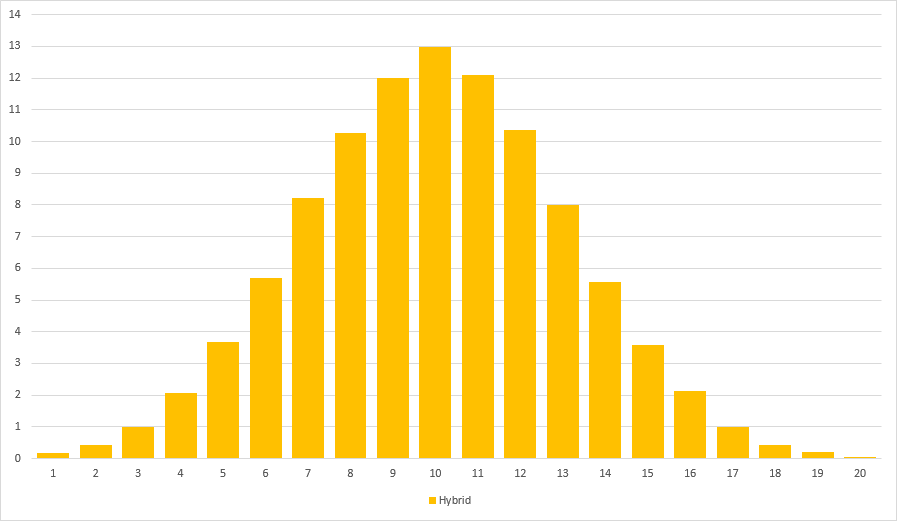

I found a value of c = 0.75 to yield very pleasing results. This is what it looks like:

Isn’t it beautiful? A nice Poisson-esque distribution spreading all the way to the left while staying bound to the right. Glorious!

Using dithering with a randomized threshold results in aesthetically pleasing distributions that match our desired goal of creating events that feel random but fair. The expected value is preserved while preventing streaks of good/bad luck.

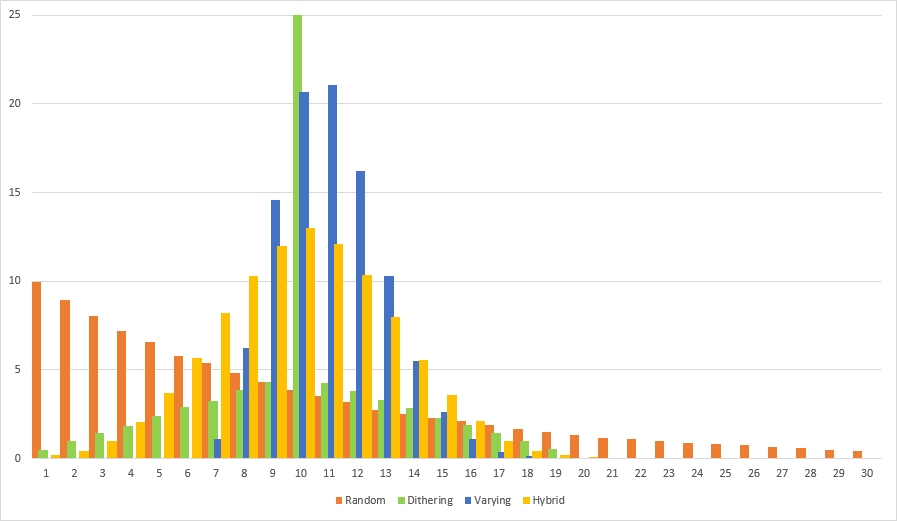

Comparison

A clear victory for the randomized threshold method, referred to as Hybrid in the graph.

In depth analysis

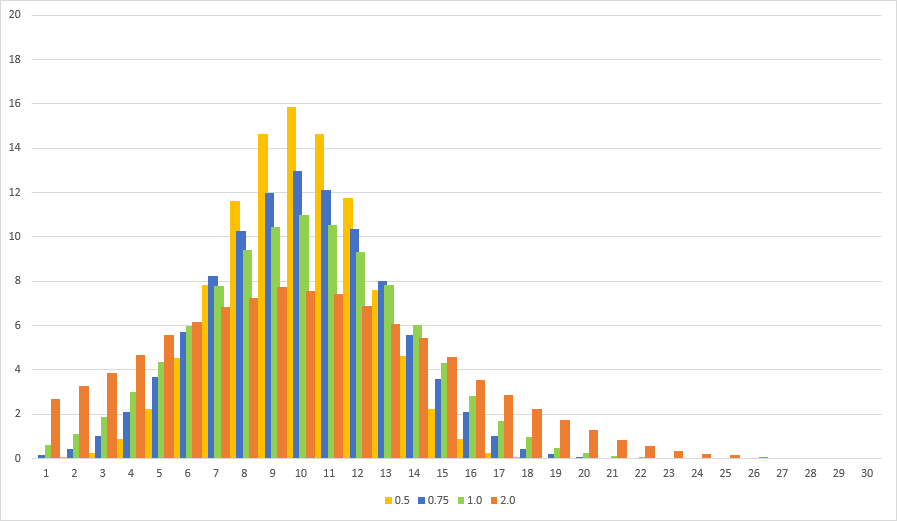

As I said before I found a threshold value of c = 0.75 to yield very pleasing results. But what does c mean? The parameter c controls the amount of randomness added to the distribution. Smaller values stay closer to the deterministic distribution, large values increase variance. A value of c >= 0.5 is necessary to allow for scoring twice in a row no matter how small the configured success probability p. Values of c > 1.0 tend to make the distribution feel too random. Here is a comparison of various values of c:

All distributions are centered around the expected value of 10. The upper bound of a streak of bad luck is determined by (1 + 2c) / p where p is the configured probability of success. In our case p = 10%. I like c = 0.75 but really anything between 0.5 and 1.0 will work depending on the desired balance between determinism and randomness.

I’ll conclude this post with an overview of distributions using c = 0.75 for varying p. You can clearly see the Poisson-esque shape of the distributions. Also the upper bound of 2.5 times the respective expected value is apparent.